Introduction

There's a quiet revolution happening inside the fastest-growing AI-native companies right now.

Not long ago, companies like Cursor, Harvey, Decagon, and Cal AI were dismissed as "GPT-wrappers," products that relied so heavily on models from frontier labs like OpenAI that many thought they would never become viable businesses of their own. To some extent, this makes sense: if the models provide the capabilities these products couldn't exist without, doesn't it stand to reason that most of the value generated would flow back to the frontier labs in one way or another?

This mindset underestimated how quickly these companies would understand that the real asset wasn't the model, but the data their users were generating. Today, all of the companies above have removed their dependence on frontier labs, trained their own language models, and are using them to power core functionality inside their products. They are investing in in-house teams and systems to improve model capabilities well into the future.

This is the future we see at Inference.net. In 2026 and beyond, more companies will realize that small, customized LLMs can match frontier quality for a fraction of the cost. The days of renting capabilities are numbered. Companies that want long-term defensibility will own their models and data flywheels that power them.

Big Token

Models like Opus 4.5, GPT-5.2, and Gemini 3 offer incredible capabilities that span a wide range of tasks. These behemoths can write code, solve decades-old math problems, and wax poetically about the nature of human consciousness. They're undoubtedly changing the world in new and interesting ways, and the leverage these models provide feels nearly unlimited, save for one small constraint: access is gated by the paywalls and policies of 'Big Token'—Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google.

You can use them, for a fee, for now. As long as you behave in the eyes of their creator, they will gladly rent you metered access to these wonderful capabilities.

Being a customer of these companies is a precarious position. If you build a product on their APIs, you are at the mercy of some of the most aggressive and growth-hungry organizations in the world. There is no limit to their aspirations, no telling when model performance would degrade without warning, and nowhere to run except into the clutches of their competitors.

The trap is threefold:

- Performance. Models change silently. You debug for days before realizing the problem isn't your code. There's no telling when model performance will degrade without warning.

- Price. Your unit economics are hostage to their pricing decisions. Some significant percentage of your revenue will be carried out the front door of your house every week.

- Policy. Terms of service change without warning. On-prem deployments cost tens of millions and are only available to the largest companies in the world.

You are feeding their flywheel. Every request you send through OpenAI or Anthropic is valuable data you're handing over for free. They'll use it to improve their models. Your competitors, also using those APIs, get the benefit.

This data doesn't just let them grow their model. It lets them specialize in your domain. They see which verticals are generating the most value, which use cases are sticky, and which markets are worth entering.

This is the world Big Token wants you to live in: Rent access to their models forever, pay by the token, and pray that they don't take a liking to your market.

The Heresy That Was DeepSeek

This changed in December 2024.

Open-source LLMs, such as DeepSeek V3 and later DeepSeek R1, put massive downward pressure on the prices Big Token could reasonably charge its customers. By offering the first viable alternative to closed-source frontier models, DeepSeek gave ambitious companies a realistic path to fine-grained control over the models powering their products in production.

Startups could swap their OpenAI usage to open-source models with a two-line code change. Larger companies began renting their own GPUs directly and deploying these models on vLLM or SGLang, expanding control over their AI infrastructure.

DeepSeek gave developers a small taste of what freedom felt like.

But it introduced new problems. By spring 2025, Big Token had produced models that were noticeably more capable. DeepSeek was more affordable, but still expensive at scale. And serverless inference providers started pushing hard to lock teams into year-long contracts in order just to access the rate limits required to run a production application.

Choose: pay a premium for the very best models, or use a cheaper model, take the quality hit, and hope your customers don't leave for a competitor who chose option one. Pay the piper, or have your product designated B-tier.

Or realize quality lies not in the underlying model, but in the underlying data. Your data.

Building Your Model Moat

2026 will be the year of the small, specialized, frontier-quality LLM. You will build it in the same way software has been built for decades: through observing from your users and iterating relentlessly.

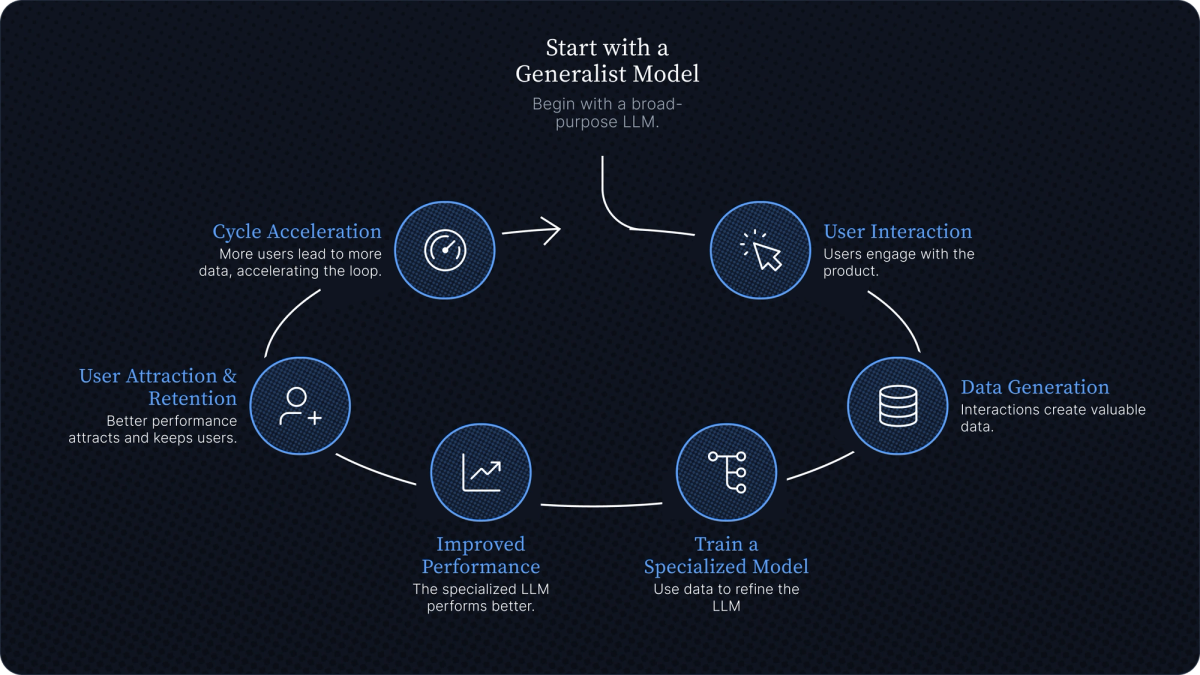

This is what we call the flywheel. The core loop works like this:

- You start with a generalist model powering your product.

- Users interact with it.

- Those interactions generate data.

- You use that data to train a specialized model.

- The specialized model performs better.

- Better performance attracts and retains users.

- More users, more data. The cycle accelerates.

This is a moat. Not a moat made of brand recognition or network effects or regulatory capture. A moat made of data that literally cannot be recreated without your application and your users.

A competitor could start with the same base model tomorrow. They could raise more money than you. But they can't conjure the dataset you've built through months of production traffic and user feedback. And if you're improving faster than they can catch up, the gap only widens.

Here's what most teams miss: if you have users, you're already generating this data. This is the easy part. The more difficult part is using that data to build an effective flywheel that compounds value back into your company over time.

The Flywheel as Product Philosophy

More than just a technical decision, building a flywheel is an entire product philosophy. Two questions should guide every decision:

- How can you design features that generate high-quality data as a natural byproduct of usage?

- How can you incentivize high-value users to provide high-quality feedback?

Every interaction becomes an opportunity to learn:

| Product Type | Signal Captured | How It Works |

|---|---|---|

| Calorie tracking app | Labeled correction examples | Users correct AI estimates, creating ground truth data for retraining |

| Coding assistant | Acceptance/rejection patterns | Tracks which suggestions get accepted, modified, or rejected by developers |

| Support bot | Resolution metrics | Measures which responses resolve issues vs. trigger escalation to humans |

Every code suggestion that gets accepted or rejected. Every support ticket that resolves or escalates. Every calorie estimate that gets corrected. It's all signal. For you.

Not all user feedback is equally valuable. A registered dietitian correcting calorie estimates is worth more than a casual user guessing. A senior engineer's code edits offer more signal than someone who just started coding.

Part of your job is figuring out who your high-value users are and designing feedback mechanisms that capture their input without being annoying. The calorie correction flow should feel like a feature, not a survey. The code acceptance signal should be implicit, not a popup asking "was this helpful?"

Your product is the flywheel. Every design decision either generates valuable data or doesn't. The next question is what you do with that data once you have it.

Post-Training Is All You Need

For years, the frontier labs have successfully pushed the narrative that training models is impossibly hard. You need a team of PhDs, months or years of iteration, and millions in GPU compute.

Convenient story. Increasingly untrue.

What Post-Training Actually Means

The term "post-training" refers to a set of techniques for enhancing the capabilities of an existing model. You take an existing open-source base model, such as DeepSeek, Nemotron, or Gemma, and teach it new tricks. The two most popular techniques are supervised fine-tuning (SFT), where you show the model examples of what you want, and reinforcement learning (RLFT), where you reward it for good outputs. Often it's both.

The most common pattern: start by distilling knowledge from a frontier generalist model like GPT-5 into a small model like Nemotron 9B using SFT. GPT-5 knows how to do your task pretty well. You generate thousands of examples using GPT-5, then train Nemotron to mimic those outputs. A 9B parameter model trained with SFT on high-quality distilled data can match the quality of GPT-5 for a specific task.

The result is a specialized model. Not a general-purpose assistant that can write poetry, debug code, and plan your vacation. Just a model that does one thing very well. Maybe it extracts structured data from invoices. Maybe it captions medical images. Maybe it scores leads based on email conversations.

Next, you can use RLFT – this is the most viable path to training a model to go beyond the capabilities of frontier models. With SFT, you're fundamentally capped by the quality of your training examples. The student can only be as good as the teacher. But with RLFT, you're rewarding outcomes instead of mimicking demonstrations. The model learns to optimize directly for what you actually care about, rather than learning to sound like something that optimizes for what you care about.

The Economics

You can train a specialized model in about an hour for a few hundred dollars. That includes the cost of data generation, compute, and evaluation. That's all you need to own the core capabilities that power your product.

Own, as in:

- The weights live on your infrastructure

- You can modify them however you want

- You're not subject to anyone's terms of service

- The model is your asset, owned by you.

Why Now?

This has been possible for a few years, but only recently has the barrier to entry been low enough for most teams to adopt. A few things were missing.

Evaluation. LLM evaluation is genuinely hard. How do you know if your custom model is actually good? For decades, this was a problem only researchers worried about. It took time for the tooling and best practices to catch up. Today, most teams use some combination of LLM-as-judge, where a frontier model grades your model's outputs, and golden datasets, hand-curated collections of examples you know are correct. The first approach scales. The second provides ground truth. You need both.

Data generation. A big part of training a specialized model is creating training data from frontier models. Running hundreds of thousands of inference calls meant setting up GPUs, managing inference batches, building or integrating with inference APIs, and formatting data for training. And even after all that work, how do you know your synthetic data actually represents the task you're training for? Recent improvements to GPT-5, Claude, Kimi K2 and other models have given us a reliable method to generate training data for a wide variety of tasks. The teachers got better, so the students can too.

Mental model. Teams treated models as static assets. Train once, deploy, move on. But products evolve. Users change. Features get added. The distribution of requests your model sees in month six looks nothing like month one. The model slowly degrades, and nobody notices until customers start complaining.

The new mental model is continuous improvement. You monitor production traffic. You compare what your model is seeing against what it was trained on. When the distribution drifts, you generate new data and retrain. The model becomes a living part of your system rather than a frozen artifact.

Building Your Model Flywheel

You want to capture your data flywheel rather than donate it to Big Token. How do you actually do it?

The core requirement is that your training pipeline needs access to production data. Inference and training don't need to live in the same system, but it helps. When production logs flow directly into training infrastructure, you eliminate the friction of moving data around, reformatting it, and keeping everything in sync. The tighter the loop, the faster you iterate.

You need subsystems that monitor and analyze production traffic automatically:

- Distribution drift, when the requests your model sees start looking different from what it was trained on

- Outliers worth investigating

- High-value corrections from users

These systems should flag issues and surface opportunities without requiring someone to manually review every data point. Some human oversight is fine. But if the loop requires constant babysitting, it won't survive contact with reality.

Retraining cadence depends on your application and data volume. Could be daily, weekly, monthly. The point is that it's a process, not an event. You're not training a model. You're operating one.

Are You Ready For Your Own Model?

If you're building an AI-native product and you're not thinking about model ownership, you're leaving value on the table.

The best teams building the fastest-growing companies are already training specialized models to power their core workflows. This doesn't mean abandoning frontier models entirely. Most companies will run specialized models alongside generalis. Specialized models handle constrained, high-volume tasks where success can be clearly defined. Generalist models handle orchestration, edge cases, and anything requiring broad world knowledge.

The bootstrapping path is straightforward. Start with generalists. Validate your product idea. Generate initial training data. Once you're spending $1,000 a month on API calls, you have enough volume to consider your first specialized model.

You don't need to boil the ocean. Pick your highest-volume, most constrained task and start there. This is where you build your own moat.

What We've Learned

We didn't arrive at these beliefs abstractly. We've spent the past year training specialized models for companies like Profound and Cal AI, learning what works and what doesn't. The patterns described above are distilled from operating real production systems processing trillions of tokens per month.

We've seen a calorie-tracking app cut inference costs by 80% while improving accuracy by 15% because user corrections were fed directly into model improvements. We've watched a coding assistant go from "occasionally useful" to "accepted 70% of the time" after three retraining cycles. The flywheel is real. The economics are real.

We've taken those learnings and built Inference Catalyst — a platform for training, inference, and monitoring designed to make flywheels possible at any scale. The platform will be available publicly in mid-February.

If any of this resonates, get in touch. We'd love to hear about what you're building.

Own your model. Scale with confidence.

Schedule a call with our research team to learn more about custom training. We'll propose a plan that beats your current SLA and unit cost.